A Fun Guide to Fungi:

Helpful Hints, Tips, and Suggestions for Mushroom Beginners

By Jonathan Kranz

I’m entering my fourth season of mushroom foraging: far from enough experience to claim any expertise, but perhaps just enough to be helpful to those starting out. For new PVMA members and other beginners, I offer the following suggestions, hints, and tips.

When to look

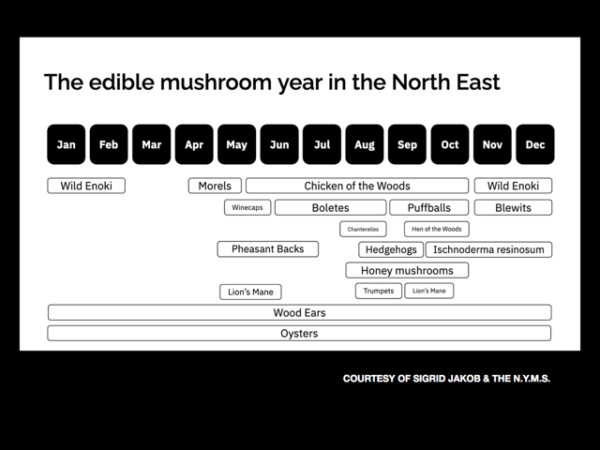

Fungi can be found year-round. But there’s a reason our walk schedule usually begins in June: in the Northeast, the cap-and-stem mushrooms that occupy the bulk of our interest generally don’t appear until then. Different regions have different seasons. In the Midwest where limestone is the dominant substrate and Elm trees proliferate, Morel-hunting starts mid-spring; west of the Rocky Mountains, winter is peak mushroom season. But for us in New England, give or take adjustments for precipitation, the season really blossoms from the 2nd week of July through the first week or two of November.

Where to look

One of the fantastic qualities of fungi is their ability to proliferate in even the most unlikely environments: on the outside walls of whiskey warehouses (Baudoinia compniacensis), in the depths of Chernobyl’s abandoned nuclear reactor (Cladosporium sphaerospermum), and in the damp recesses of our own homes (Peziza domiciliana).

But for the cap-and-stem mushrooms we’re most eager to find, fields and forests (especially forests) will be the most productive environments to explore. A few pointers:

But for the cap-and-stem mushrooms we’re most eager to find, fields and forests (especially forests) will be the most productive environments to explore. A few pointers:

- Among woodlands, generally the older the better. Look for trails among mature oaks, birches, beeches, pines, and hemlocks. Maples are common, but they find their fungal partners among the “arbuscular mycorrhiza” that do not produce the fruiting bodies we seek. Be aware of terrain: shaded, damp areas on north-facing slopes or low-lying wetlands will tend to be more productive than hot, dry turf on south-facing slopes or uplands.

- Grassy areas can yield treasures such as the Agaricus campestris (“Meadow Mushroom”) and the Marasmius oreades (“Fairy Ring Mushroom”). But remember that mushrooms tend to absorb the chemicals they find in their local substrates; if you’re looking for edibles, beware of treated lawns, like golf courses.

- HINT: Most cemeteries/graveyards have discrete waste areas where they dispose old wreathes, pruned limbs, grass cuttings, and other organic litter. These are often excellent hunting grounds for many mushrooms. The cemetery grounds themselves often include mature oaks and other species ideal for many mycorrhizal fungi (living in a symbiotic relationship with root systems), but remember the above warning about chemicals, i.e., pesticides and herbicides. For mushroom hunters, weeds are a welcome presence; if you see many, it suggests that the earth has not been chemically treated.

Edibility

Club forays typically conclude at a table loaded with finds that a designated identification expert will describe. Inevitably, someone will pick up a decaying mess – swirling with flies, crawling with pale larvae on mushy, bruised tissue – and ask, “Is this edible?”

Sigh. If you wouldn’t purchase a similarly distressed specimen from your supermarket, why would you eat it from a forest floor? More importantly, you have to build your basic identification skills. Nope, mobile apps and the opinions of obscure social media influencers on YouTube won’t cut it. To safely enjoy edible mushrooms, you need to know two things:

Sigh. If you wouldn’t purchase a similarly distressed specimen from your supermarket, why would you eat it from a forest floor? More importantly, you have to build your basic identification skills. Nope, mobile apps and the opinions of obscure social media influencers on YouTube won’t cut it. To safely enjoy edible mushrooms, you need to know two things:

- The precise features and characteristics of the edibles you want to eat, AND…

- The precise features and characteristics of the look-alike toxic mushrooms you don’t want to eat!

For example, the popular and common Chanterelle, (Cantharellus flavus, or C. cibarius) is a delicious, golden-yellow mushroom with decurrent (running down the stem) gills. The poisonous Omphalotus illudens (“Jack O’Lantern”) is also yellowish with decurrent gills. Note that the Chantarelle doesn’t have true gills, but bluntly rounded folds versus the sharper gill “blades” of O. illudens, and the latter mushroom tends to grow on wood in clusters and has a more orangey appearance overall.

There’s much more to learn about edibility, but for a guiding principle, we can keep things simple: When in doubt, throw it out.

Harvesting mushrooms

Remove your mushrooms with care. The base of the mushroom, the lowest part of the stem that meets or is anchored in the substrate, can be an important identification characteristic. The base’s shape, size, color, texture – even the presence and color of mycelium – can all be keys to your mushroom’s identity. To remove the mushroom intact, reach down and around the base with your fingers and/or an available tool, such as a knife. (I’ve been using a garden weeder; it can go deep without disturbing much of the underlying substrate.)

Remove your mushrooms with care. The base of the mushroom, the lowest part of the stem that meets or is anchored in the substrate, can be an important identification characteristic. The base’s shape, size, color, texture – even the presence and color of mycelium – can all be keys to your mushroom’s identity. To remove the mushroom intact, reach down and around the base with your fingers and/or an available tool, such as a knife. (I’ve been using a garden weeder; it can go deep without disturbing much of the underlying substrate.)

But if you’re harvesting mushrooms to eat and you’re absolutely certain of their identity, you’ll want to cut them neatly near the ground, leaving the base – and all the debris around it — behind. That way you won’t contaminate your edibles with dirt that would have to be cleaned from their gills or pores.

To protect your finds while carrying them in your basket, consider using wax paper or small brown bags. The wrapping helps retain moisture while preventing your mushrooms from getting crushed.

Books and web resources

Beginners often ask for the “best” mushroom guide. Truth is, no one book will do – you’ll need several and, if you’re like most of us, will eagerly (if somewhat guiltily) accumulate quite a library of references.

That said, I do have some recommendations. Go to any mushroom meet in which participants are encouraged to bring their own books and you’ll almost always find this particular reference over and over again, often with frayed covers barely attached with packing tape: David Arora’s Mushrooms Demystified. Yes, it’s old (2nd edition, 1986) and biased toward west coast species, but…it contains outstanding keys, excellent species and genera descriptions, and important general information for beginners. Because of the clarity of its keys, I often start with Arora to arrive at genus, then use a regional guide and/or a genus/family-specific guide to get to species.

For guides specific to our area, I suggest Mushrooms of the Northeast by Teresa Marrone and Walt Sturgeon, and Mushrooms of the Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada by Timothy J. Baroni. The former is an easy-to-carry compact guide expressly intended for beginners; its use of icons to label seasons and habitats, plus green bold print to highlight the most important ID characteristics, make it especially helpful. It also has a “top edibles” section and emphasizes the toxic look-alikes for each one. The Baroni book is bigger, presents a wider range of species, and includes deeper details (including spore characteristics) for those with a more scientific bent, making it a favorite of many PVMA members.

For guides specific to our area, I suggest Mushrooms of the Northeast by Teresa Marrone and Walt Sturgeon, and Mushrooms of the Northeastern United States and Eastern Canada by Timothy J. Baroni. The former is an easy-to-carry compact guide expressly intended for beginners; its use of icons to label seasons and habitats, plus green bold print to highlight the most important ID characteristics, make it especially helpful. It also has a “top edibles” section and emphasizes the toxic look-alikes for each one. The Baroni book is bigger, presents a wider range of species, and includes deeper details (including spore characteristics) for those with a more scientific bent, making it a favorite of many PVMA members.

I also recommend getting your hands on Mushrooms of North America by Roger Phillips. At first, the book’s photographic approach turned me off. Instead of presenting mushrooms in situ, within the beautiful habitats they occupy, Phillips presents his species on neutral gray-blue backgrounds. But I quickly learned that this liability is truly its virtue: although less sexy, Phillips’ photography captures reality – what your specimens will actually look like by the time you go to your table and start identifying your finds. I’d begin with the other three books but encourage you to seek a used copy of Phillips online. (I got mine in decent condition for only $10.)

In addition to these references, you may want to explore genus-specific guides for those genera that particularly interest you. Our area is so rich in boletes, for example, that I’ve found Boletes of Northeastern North America by Bessette, Bessette, and Roody, to be practically essential. Our own chief mycologist and club co-founder, Dianna Smith, recently published (with the above mentioned Bessettes), Polypores and Similar Fungi of Eastern and Central North America in 2021, an outstanding guide to the unusual mushrooms that persist year-round in our woods and on our decaying logs.

For a more comprehensive list of vetted books, see the list Dianna compiled at https://www.pvmamyco.org/field-guides.

For web resources, begin with our club site, PVMAmyco.org and Dianna’s widely respected project, FungiKingdom.org. Caution: FungiKingdom.org will suck you into its depths; before you enter, be prepared with sufficient snacks and potables. This is one of the best places on the web for trustworthy mushroom education.

In addition, I’m fond of Michael Kuo’s MushroomExpert.com for its in-depth descriptions and continually updated mushroom nomenclature. (Inexpensive DNA analyses have led to a dramatic reshuffling and renaming of many species; I expect that by the time I type the last of this sentence, two or three of my favorite mushrooms will have changed names.) My last web recommendation is a little offbeat considering that I cannot speak French: MycoQuebec.org. Why bother with a reference in a foreign language? Because MycoQuebec presents more photographs per species than any other site I know of – a truly handy feature given the many ways a single species may appear given weather, age, exposure to sunlight, and other variables. Also, adjectives dominate the descriptions, and these are relatively easy to understand in context.

Mushroom identification and taking notes

Mushrooming doubles your fun. We follow the joy of the outdoor hunt with the satisfaction (tempered with frustration, as you’ll soon see) of identifying what we’ve found, usually with the help of reference resources. Basically, identification is a two-part process of 1) close observation and 2) matching observed features to the definitive characteristics recorded in the scientific literature – in our case, mostly field guides and websites.

Important note: You won’t be able to identify everything you find — even the experts are occasionally stumped. Your finds might not be represented in your resources; aging, weather and other conditions may render your specimen unrecognizable; but most frequently, you’ll come across fungi that cannot be identified by macroscopic means (what you can see without the aid of a microscope) and require microscopic examination and/or DNA analysis.

Important note: You won’t be able to identify everything you find — even the experts are occasionally stumped. Your finds might not be represented in your resources; aging, weather and other conditions may render your specimen unrecognizable; but most frequently, you’ll come across fungi that cannot be identified by macroscopic means (what you can see without the aid of a microscope) and require microscopic examination and/or DNA analysis.

While you’re in the field, take pictures! You want to capture as much identifying information as possible, so be sure to include the substrate around the mushroom body. Photograph the underside of the cap to get a good look at the fertile surface (e.g., gills, pores, teeth), and capture as much of the stem as you can. If you’re fortunate enough to find multiple specimens of the same species, see if you can photograph the full fruiting body lifecycle from emerging “egg” to unfolding cap, through maturity and into early decay.

Back at home or lab, successful identification begins with excellent notetaking. Before you crack open your books, get out your pencil and record, to the best of your ability, the following points:

- Date of harvesting: Your future self will thank you because these dates help you learn and remember the seasonal rhythms of fungal fruiting.

- Location: Where did you find it?

- Habitat and environment: Again, location, but with more local detail. Did you find it in a field or forest? If the latter, what kind of trees were nearby? Was it found in a dry upland or a damp wetland?

- Substrate: What was the mushroom growing on? Ground near trees? Open grasslands? On decaying stumps or branches? Moss? Other mushrooms?

- “Social” characteristics: Was your mushroom solitary? Grouped near others? In a ring or line? Or even clustered with other mushrooms at the base?

- Spore print: What color are the spores? Many keys – a diagnostic “process of elimination” for identifying specimens – start with spore color, so it’s important to know. HINT: Before you pick a mushroom, look around; often you’ll find spore deposits on the substrate under the mushroom, sometimes even on the caps of nearby fruiting bodies.

- Cap characteristics: What’s the diameter? How about the shape: like a bell, a cone, or flat (planar), etc.? Check the texture: does is have “hairs” (fibrils)? Is it sticky or gooey? Dry, rough, or smooth? Check the margin: does the cap stop where it meets the fertile surface (“even”) or do you see a thin edge of loose, sterile tissue? Any other tissue hanging from the cap? Any “warts” or remains of the universal veil (common among Amanitas, for example)? Of course, you should record color, but of all the cap characteristics, color is the most problematic as color can change with age, weather, and other conditions.

- Cap flesh: What’s the color? Does it change when it’s cut? How thick is it?

- Aroma/scent: Any distinctive smells? Some common ones include flour/yeast, cucumbers, rotting fish, watermelon, and plain old “mushroom.” Uncommon ones include ashtrays (Hemileccinum rubropunctum) and rocket fuel or skunk cabbage (Phyllotopsis nidulans).

- Fertile surface (gills, pores, teeth) qualities: Do you see gills, pores, or teeth? If gills, are they densely packed or far apart or somewhere in-between? Are they broad or shallow? Does the edge have color? Most importantly, how are they attached (or not) to the stem? Are they “free” (not attached), fully attached (adnate), barely attached (adnexed), notched near the stem, or even running down part of the stem (decurrent)? What color are they? What’s their texture: brittle, waxy, greasy? If you cut or bruise them, do they change color? Do they exude a liquid (“latex”) when cut? Any partial gills or forking? If you see pores, are they tiny and packed or large and angular? Again, what color are they, and does the color change with handling?

- Stem/stipe: How long and thick is it? Is it uniform along its length (“even”) or does it enlarge toward the apex (top) or base (bottom)? What’s its color? Do you see any particular textures, like reticulation (raised lines), punctae (raised dots) or chevrons (a snakeskin quality)? When you cut it, do you find it solid, hollow, or “stuffed” (loosely packed with material)? If you see larval tunnels, what color are they? Look at the bottom: does it have a bulb? A club shape? A “pinched” quality? Any remains of the universal veil (“volva”)? Any mycelium (fungal threads) attached? What color are they? How is the stem attached to the cap? Centered, off-centered, or missing altogether (“sessile”)?

- Ring/annulus: Back to the stem: does it have a “ring” or ring remnants on it? Any dangling threads? Is the ring big and floppy, or barely visible?

If all this seems like a lot, it is – and there’s far more to observe and record. Consider the above as a mere starting point. As you grow in experience, both your mushroom vocabulary and your powers of observation will improve – that’s part of the pleasure of the process.

Finally, a few thoughts on mycological etiquette and foray behavior. Learn from the more experienced mycologists around you. It’s generally considered bad form to ask for specific locations of prized mushrooms, but you’re always encouraged to ask questions about mushroom characteristics and identifying features.

Finally, a few thoughts on mycological etiquette and foray behavior. Learn from the more experienced mycologists around you. It’s generally considered bad form to ask for specific locations of prized mushrooms, but you’re always encouraged to ask questions about mushroom characteristics and identifying features.

Watch where you walk. Our sturdy oaks and pines are complemented by more fragile growth – mosses, ferns, lichens, wildflowers, and more – that suffer under our feet. When you see litter, pick it up; we like to leave our foray sites cleaner than before we arrived. When we find edibles, we share. (In one of our early forays last season, we found a mother-load of Laetiporus sulphureus, aka, “Chicken of the Woods,” on a large standing snag. Even though we left much of it on the tree, everyone who wanted a share got enough to make a substantial meal.) As a last, finger-wagging injunction, please never collect everything available; leave some behind to allow the fungus to be fruitful and multiply.

Let’s begin. Go outside, get your hands dirty, and fill your notebooks with observations. The fungal world awaits.